Jack Roseman says anti-Semitism was pervasive when he was growing up in Lynn. One incident, nearly 68 years ago, still rankles.

“I was in the eleventh grade at Classical High,” he said. “I left my notebook at home. A classmate let me use a tiny, little notebook he had. I’m in class, writing in this little notebook, and the chemistry teacher, Mr. Hutchins, I’ll never forget his name, sees me writing in this tiny book and yells out ‘Why are you people always so cheap?’ I was 18 years old. I’ve never gotten over it.”

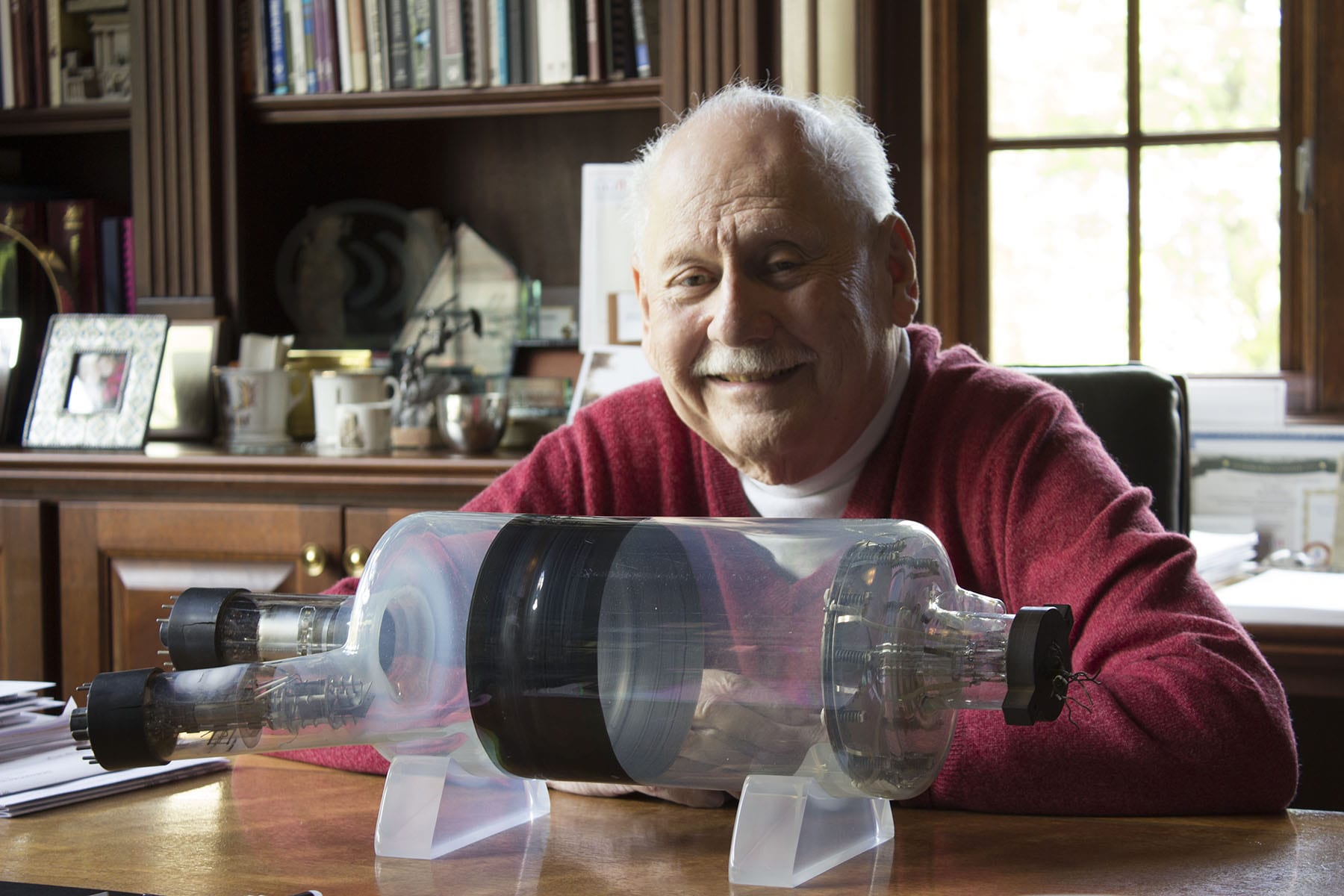

Roseman chronicles his life in “Jump! How I Rose from Poverty and Anti-Semitism to Become a Tech Sector Pioneer and a Mensch,” his new, inspirational, entertaining memoir that explores his growing up poor in Lynn and how it and prejudice toward him and other Jews drove him to succeed in life.

And succeed he did, eventually launching and running several tech businesses, and serving as professor of entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon University.

“Lynn is the saddest part of my life,” he said. “It was terrible. We lived in abject poverty and I was tormented by anti-Semitic bullies. Our house was a sad place. My oldest brother Leibel and his family and my mother’s sisters were murdered by Nazis in our native Ukraine. My other brother Hy, also older, had many childhood diseases, including Scarlet Fever, and had a bum leg. My father didn’t work for much of the year. My mother was a tough woman and not very loving. It was a bleak childhood.

“I grew up in a mixed ghetto on Summer Circle. It was a rental in a six-unit building. We were on the second floor. We had five rooms, a kitchen, a parlor, and three bedrooms—one for my parents, one for my sister Lena, and the third for Hy and me; we shared a bed until he went to college. The apartment had a unique central heating system: the stove, and it was our only source of heat. The building is gone now. Tobin’s Egg Store was on the corner. About 20 years ago, I brought my wife to Lynn to show her where I grew up. It had been leveled,” said Roseman from his Pittsburgh home.

“I look out my window here and I see trees, rabbits, deer. I ask myself ‘How did I get here?’ whenever I remember looking out my window in Lynn and seeing rats.”

A recurring nightmare also haunts Roseman to this day.

“It started when I was about 10. I’m standing at the top of a stairway. My mother is at the bottom telling me to jump. She’s standing at the bottom, with her arms out as if she’s going to catch me. I jump. She just stands there. She walks away and says ‘Never rely on anyone. Not even your mother.’ That became my mantra: ‘Never rely on anyone. Do it yourself if you must, but do it.'”

“That’s the purpose of the book. This is what I did to get out. You can, too. Everybody, at at least one point in their life, will be faced with a decision. Do you stay put or do you take the leap into a promising, frightening future. My advice is to jump.”

Roseman’s “business career” began with a hot-dog stand run by him and two buddies at Revere Beach and a job at the long-gone Howard Johnson’s restaurant on Route 1 in Lynnfield. He started as a pot washer, and kept getting promoted whenever someone quit or was fired, eventually rising to short order cook and chef even though his culinary skills were non-existent. He turned down the opportunity to manage the HoJo’s in Revere, opting for college. A wise choice, in hindsight. In the nascent days of computer programming, math whiz Roseman landed jobs at MIT, General Electric in Schenectady, and eventually founded and ran several successful tech companies.

One day, Jack and brother Hy were alone in the house. “He said to me ‘Jack, there are very few Rosemans who can make us proud. It’s too late for me, and Dad isn’t going to do it. It’s up to you Jack.’ He put a ton of bricks on my back.”

That pressure to make something of his life and prove the anti-Semites wrong nearly killed him. Overwork and stress caused a bleeding ulcer in his 20s and a massive heart attack in 1972. “They told my wife, Judy, I had one night to live. Hy came to my hospital bed and whispered in my ear, telling me not to worry about making the name Roseman mean something. I said ‘Dear brother, it’s too late.'”

Jack and Judy had a storybook romance, raised three children, have enjoyed spending time with their five grandchildren and recently celebrated their 58th anniversary. Judy, fearful her husband would die early, continued her schooling, earned a Master’s and is successful in her own right.

“I, we, have had a very good, fulfilling life,” Roseman said, who last visited Lynn about 10 years ago when his late sister Lena’s health was failing. Lena and her husband never left the city, raising two children here.

Does Roseman have a bucket list? “No bucket list. Just a f***-it list; if something is out of my control I don’t get upset, I just say ‘f***-it.”

“I will take every day as it comes. I have lived a lot longer than I ever thought I would. Of course, one day I will die, but I won’t die unhappy.

“I wrote about my improbable journey for one reason, to inspire others to break out of their ghettos, whether they be economic ghettos or prisons of personal doubt.”