Even now, 50 years later, Judy Wayne’s jaw drops to the floor as she contemplates the three days she spent on Max Yasgur’s farm in Bethel, N.Y.

“I think about it,” the Lynn attorney said, “and I can’t believe that I was even there.”

“There,” of course, is the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival — perhaps the last gasp of a decade that, by then, had very badly veered off course.

The Summer of ’69 is more than simply a Bryan Adams song. Events happened at dizzying speed. First, Apollo 11 was launched and astronauts landed on the moon. Then came the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s tragic accident that claimed the life of Mary Jo Kopechne and also, perhaps, altered the course of U.S. political history.

On Aug. 8 and 9, Charles Manson and his off-kilter cult went on its notorious killing spree in the Los Angeles hills, shocking with both its brutality and senselessness the same nation that had been giddy with pride only a month earlier.

Into this maelstrom came Woodstock, a three-day bacchanale of music and drugs on Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel (47 miles southwest as the crow flies from Woodstock). That was when the tie-dyed nation of Baby Boomers, or at least upwards to 400,000 of them, gathered as one tribe and became giddy on something else.

Wayne was just out of high school and about to enter her freshman year at Northeastern.

“I was probably one of the younger ones there,” she said, adding that she was not among the drug-users there (“it just wasn’t my thing”).

“I didn’t even have a ticket,” said Wayne, who practices in Lynn and lives in Marblehead. “When I mentioned that to the guy who was driving us there, he said it didn’t matter. We’d figure something out.”

Wayne grew up in Pittsfield, a mere two hours from where Bethel is in upstate New York. And, being from the Berkshires, music was a large part of her life.

“Both my parents were musicians,” she said, “And some of the country’s best musicians were from that area, or came to that area.”

She had no idea what to expect, so when she got to Bethel, she was overwhelmed.

“I had no idea there would be that many people,” said Wayne. She was used to sitting outdoors listening to music at places like Tanglewood.

But this?

“There was no place to eat, no place to sleep, no place to go to the bathroom, and no place to get in out of the rain,” she said. “And it didn’t matter. The music made it all worthwhile.

“Every one of my favorite groups played there,” she said. She specifically remembered Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers,” because afterward, “we’d all put our speakers near the windows of our dorms, so that the music would blast out into the street, and all you heard was that song.”

There were two distinct schools of thought leading up to Woodstock. The pessimists were convinced that a scene with thousands of young hippies (the word had faded from use, but nobody told that to the farmers in Bethel who tried to block the concert) assembling in a big field, with loud rock ‘n’ roll music blaring day and night, with drugs that probably didn’t even have names yet, would lead to anything good.

The optimists sang a different tune. We will have enough food, they said. We will have first-aid stations for those who suffer bad drug experiences. It’ll be a peaceful three days because we’re spreading that vibe.

That’s exactly what happened.

“Everybody shared,” Wayne said. “If you had food, you put it out and shared it with other people. There were portable toilets (though not nearly enough of them. The lines were enormous, Wayne said), people helped each other out. It was amazing.”

All wasn’t copacetic, of course. There was Arlo Guthrie stating from the stage that “they’ve closed the New York State Thruway, man” because of the gridlocked traffic. And, notes Wayne, “they would make announcements over the loudspeaker telling you not to take this color acid, or that color of speed, because it was poison.”

With all that, it really was peace, love and music, she said.

“It was day-and-night music,” she said. “That was the amazing part. It was constant. Imagine, going to a concert with Crosby, Stills and Nash, The Who, the Airplane … it doesn’t happen today. It couldn’t happen today.”

Every time someone tries to replicate it, she said, something invariably goes wrong.

There were only three recorded deaths — two by overdoses and of one man who was run over by a tractor while in his sleeping bag.

Even when it rained sheets, which it did more-than-intermittently throughout the weekend, there were no incidents. Some of the concert-goers actually played in the mud.

“Those who got there early enough could park near enough to the field,” she said. “There were a lot of Volkswagen buses with flowers and things painted on them. People would pile in to get out of the rain.”

Woodstock ended up springing to stardom quite a few of the acts that played there. Crosby, Stills and Nash’s acoustic performance of “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” is iconic, thanks mostly to the movie and Stills’ ad libbed “we’re scared (expletive)” afterward.

Country Joe McDonald was just a singer of quirky songs until he performed “The Fish Cheer” and the “I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.” There’s a litany of other singers and groups who made their careers in the rain and mud of Woodstock, among them Ten Years After and Santana.

Ironically, one who did not was Joni Mitchell. She never made it up there. But she wrote the song that chronicled it.

Wayne remembers all of it, from Ritchie Havens to Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” that echoed throughout the half-empty field.

“Nobody spoke all the way home,” she said. “We were tired, we were hungry, and we were soaked. But more than anything, we still had to process what we’d seen. It was amazing.”

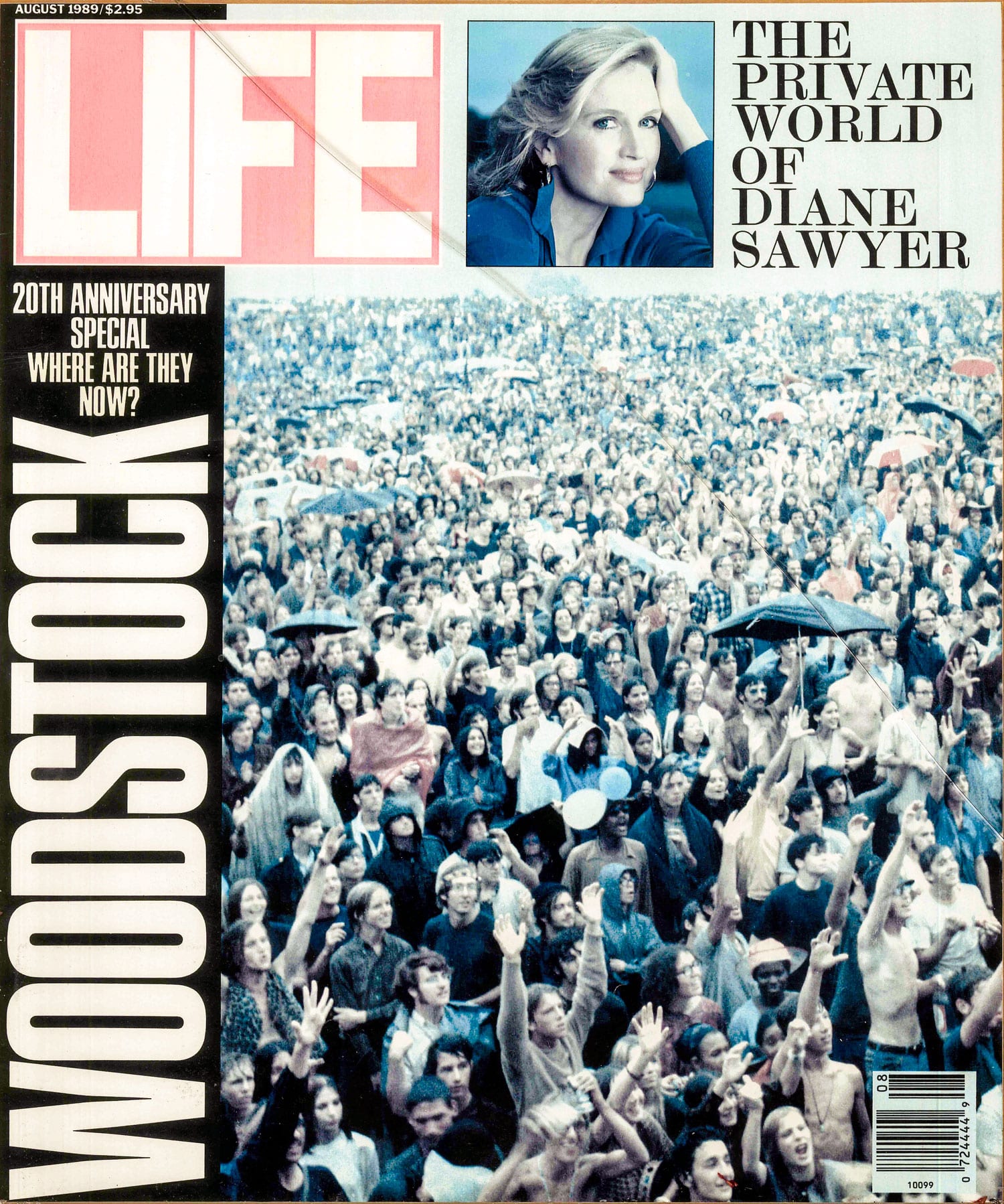

On the festival’s 20th anniversary, Life Magazine’s cover showed a mass of humanity listening to a concert in the rain (umbrellas were visible). In it, standing while wearing a blue denim jacket, with her hair soaking wet, and her hands clasped as if she was either praying or clapping, was Judy Wayne.

“I looked at it and said, ‘Hey! That’s me!’ “