There’s a bit of a fallacy in the revisionism that Bobby Orr’s iconic Stanley Cup-winning goal 50 years ago Sunday was all that important.

It wasn’t as important as it was memorable. In fact, it wasn’t important at all.

David Ortiz’s 12th inning home run in Game 4 against the New York Yankees in 2004 was important (in its context, of course). Carlton Fisk’s 12th inning home run in Game 6 of the 1975 World Series was important. John Havlicek’s famous steal in 1965 was important. And Adam Vinatieri made the most important kick in Patriots history not in overtime of the 2002 playoff game against Oakland, or in the last seconds of two Super Bowls, but in the waning seconds of regulation in that Raiders game.

Those were truly historic. In all of the above cases, it was win or go home.

Orr’s goal may have been the culmination of years of promise and frustration, but it does not reach the same level of importance. The Bruins still had three more shots to win the Stanley Cup, and there was no way they were going to lose it.

Let’s go back and examine.

The Bruins were on a roll. By the time they swept into the Stanley Cup finals, they’d beaten the only two teams capable of competing with them — the New York Rangers in six games, and then the Chicago Blackhawks in four.

By Mother’s Day, They were up 3-0 in games over the St. Louis Blues, a third-year expansion team with a goalie (Glenn Hall) who was 38 years old. Even the best of those original expansion teams were no match for any of the Original Sixers over the course of a long series.

Game 4, at the Boston Garden, was a tug-of-war — unlike the other three games (the scores were 6-1, 6-2 and 4-1). After regulation it was 3-3 but if there was any palpable apprehension over the impending overtime, I didn’t feel it at 18 Bonavesta Street in Lynn.

I was 16, a junior in high school, and the only thing I knew was that finally … finally! … these guys were going to win the cup after being tormented by the Montreal Canadiens for the previous two seasons. If it was on Sunday or the following Tuesday, or sometime after that, it was going to happen. There was no way a team with Bobby Orr, Phil Esposito, Gerry Cheevers, and the rest, were going to lose four straight games to the expansion Blues.

I’ve watched many overtime hockey games and I’ve done my share of fidgeting and pacing, but not in 1970. I did go into the kitchen to get something to eat. It being Mother’s Day, there was probably some kind of a dessert just waiting to be eaten.

The point is, I was not worried. It just did not seem possible to me that the Bruins would lose.

The one thing I do remember, all those many years ago, is that it must have been some snack. I barely got back onto the couch before the period started. I wasn’t even settled when the goal happened. And when it did, it happened so quickly that I missed it.

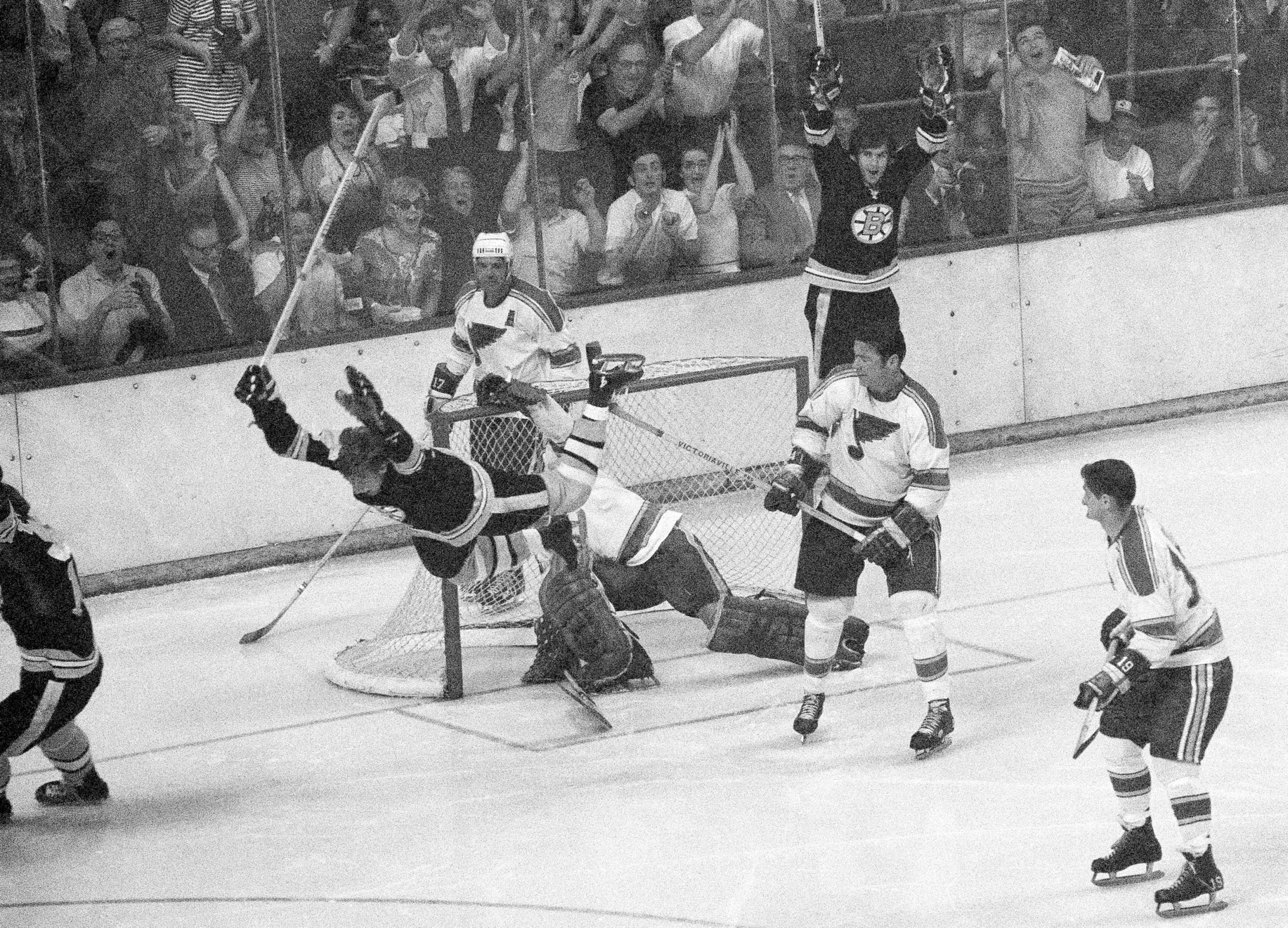

I don’t remember why I missed it. Maybe I was looking down at the sandwich I’d just made, or maybe I was in the middle of taking a sip of my Coca Cola. But whatever, I just heard “Score! Bobby Orr!” and looked up in time to see No. 4 flying through the air. Everything after that — the pig pile, the ceremony — was a blur. I don’t even remember seeing a replay of the goal until much later that day.

This is going to sound heretical, but I didn’t want it to be Orr who scored the goal. Orr was the best hockey player I ever saw, Gretzky me no Gretzkys. He took the Bruins from perennial out-of-the-money status to Stanley Cup winners almost all by himself. I’d go as far as saying that he controlled the game even while he was between shifts because he forced the opposition into matchups that didn’t favor them when other Bruins were on the ice.

But it was beginning to feel like I should genuflect and bow my head at the mention of his name.

I was very happy, though, that it was Derek Sanderson who set the goal up with that give-and-go play. As a teenager in the 1960s, Sanderson’s counterculture pretensions appealed to me. I know he wasn’t Joe Namath. But he was a reasonable facsimile.

But when it was all over, I was just happy they won. These Bruins were bigger, even, than the Red Sox or Patriots were/are. They owned the town like nobody’s ever owned it.

Orr’s goal, and that Stanley Cup, were validation of all the hype and excitement that had been building since he broke in as a rookie in 1966. And in that sense, the goal was historic.

But there was nothing unusual or desperate about it. And more to the point, its defining image — Orr flying through the air — was an accident, albeit a happy one. He’d been tripped just before he shot the puck.