And to think, at the exact moment Henry Aaron hit Al Downing’s pitch over the left field fence in Atlanta, I was taking the dog in the house. I didn’t even see it.

Like most real baseball fans in 1974, I was pulling for Hammerin’ Hank to hit his 715th home run as quickly as possible. The modern celebrity era was well underway by 1974. Not only that, phony, made-for-TV celebrity was already well established. Later that summer, Evel Knieval would attempt to jump his motorcycle over the Snake River Canyon in Idaho (and fail). And as the years have progressed, we’ve completely lost our ability to distinguish between real and fabricated.

But in 1974, Henry Aaron, who died Friday, was as genuine as it got. Among the first wave of Black athletes who hit the Major Leagues after Jackie Robinson’s groundbreaking debut, Aaron broke in with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 — two years after they left Boston (much to my father’s everlasting chagrin). He was, however, the antithesis of the hard-driving Robinson. He was a smooth, line-drive type hitter who basically showed up and played. By the late 1950s, he was in the middle of a Braves lineup that included Joe Adcock and Eddie Mathews, and who won two National League pennants and a World Series.

In a 23-year career, Aaron hit 755 homers, and never — not even once — hit 50 in a season. He finished with a lifetime batting average of .305, and if anyone doubts his authenticity as one of the game’s legends (and I’d like to meet that person), just know that the great Bob Gibson, who wrote the book on being competitive, said that Aaron was the toughest hitter he ever faced.

But as good a player as Aaron was, he was a better man. And this, really, is the story about a man who was thrust in front of the spotlight during the infancy of overwhelming celebrity — without the protections afforded to modern-day superstars — and he not only came out of it intact, he taught us all a few things about humility and dignity.

Understand this: Tom Brady is definitely among the most sought-after superstars of this era. Wherever he goes, he’s followed by a national horde of media. His time is managed, his media sessions organized about as well as any presidential news conference, and he is cloistered far, far away from the media madness at all other times.

Aaron did not have that luxury. He was a Black man challenging one of the most sacred baseball records of all time, established by a white icon. And he was on his own.

Back then, when you wrote the book on baseball legends, Babe Ruth and his 714 home runs constituted the first chapter. Even white players, such as Roger Maris, who dared approach the Bambino’s hallowed hitting records were subjected to enormous — and unfair — scrutiny. Imagine what it must have been like chasing a white player’s record while Black.

Not that it really needs to be pointed out, but I’ll point it out anyway. Ruth was not a good person. He was a carouser, a womanizer, went through large stretches of being in terrible physical condition, and had legendary feuds with managers. The Red Sox couldn’t wait to ship him out of town just when he was approaching his peak years, and it wasn’t because of “No, No, Nanette.” Owner Harry Frazee just didn’t want to babysit him anymore.

Contrast that with Aaron. Never an incident. All he did was play, and play well. And handle himself with class and dignity. Yet the unjust grief he had to take for challenging that record of 714 career home runs was unconscionable, the things he endured — the racially-charged hate mail, the death threats.

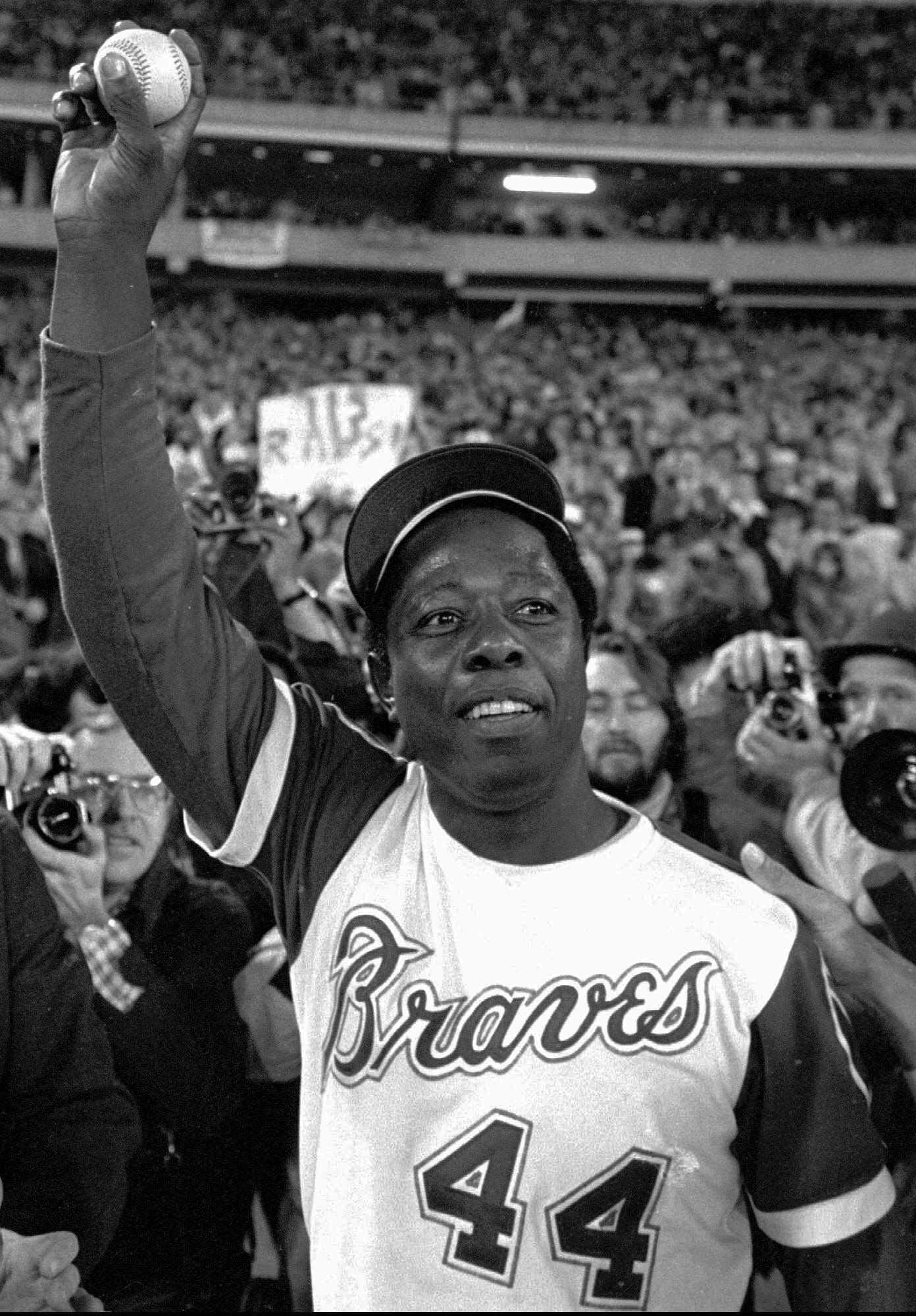

In the face of all that, Henry Aaron endured. He broke Ruth’s record in a home game with the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974. And between innings, I went to the back door to let the dog in. When I got back to the TV room, I could hear Curt Gowdy scream “He did it! He did it!” and saw Aaron circling the bases. Thank heavens for replay. I’ve only seen it about a thousand times since. And I even went to the Newseum in Washington and did my own voiceover for posterity.

Years later, on Aug. 7, 2007, the arrogant Barry Bonds, who, by most accounts, cheated to get into the position, broke Henry Aaron’s record of 755 home runs. If Aaron was the antithesis of Jackie Robinson, then Bonds was the antithesis of Hank Aaron. Controversy walked alongside Bonds at all times. He acted boorishly. And in my eyes, he besmirched everything Henry Aaron ever stood for in the game.

Make no mistake. Henry Aaron was one of the all-time greats. But he was a better person. And that matters more.