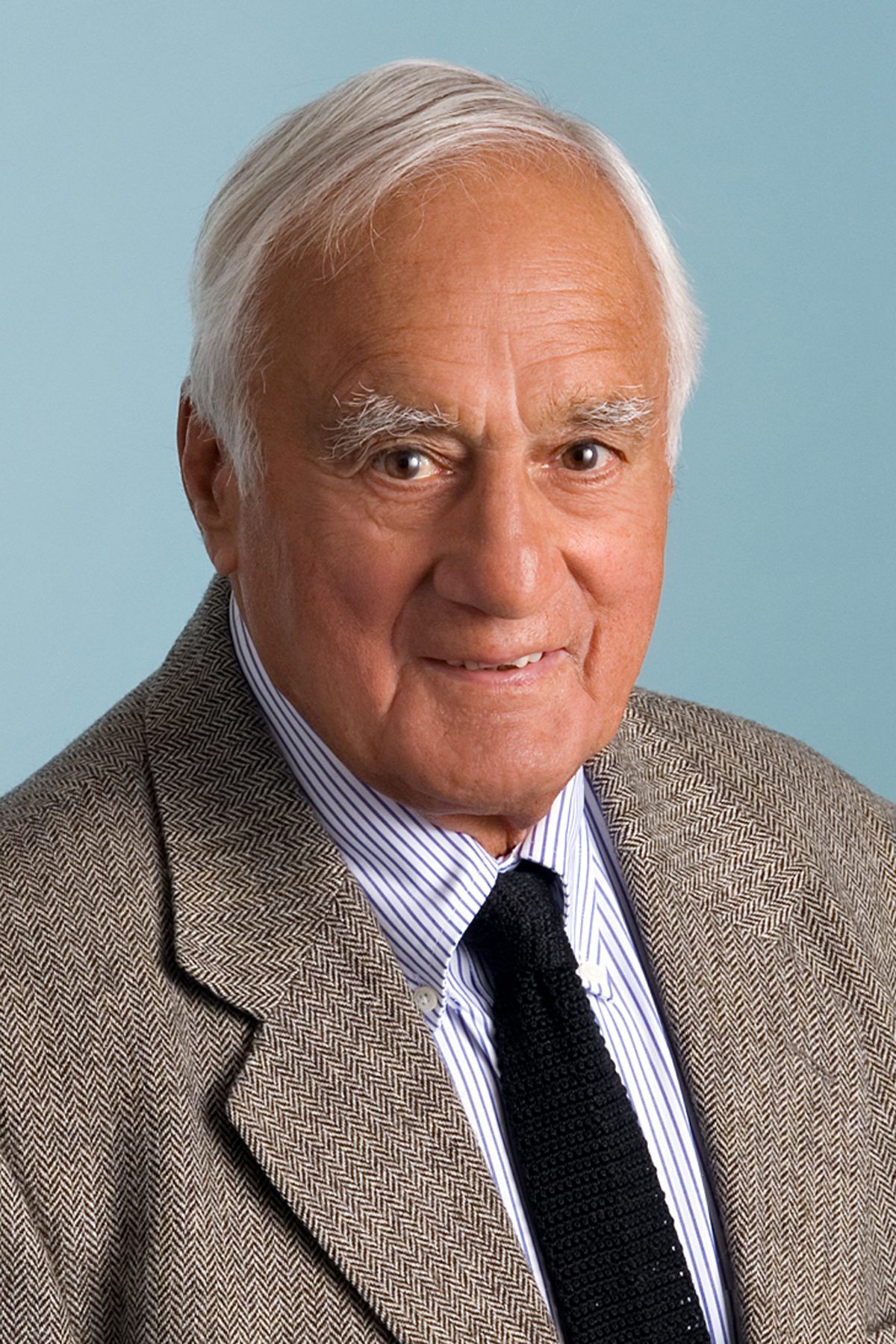

In less than two years, Francis X. Bellotti will turn 100. But the Boston College Law School graduate, who was first elected to public office in 1962 as lieutenant governor of Massachusetts and later as attorney general, has yet to slow down.

Decades after he led his 58-man squadron in World War II and following three terms as the state’s top cop, the father of 12 has yet to retire. He still can be reached most days at Arbella Insurance Group, the Quincy-based company he co-founded in the 1980s. He is also a part-time practitioner at the Boston law firm of Mintz, Levin, Cohn, Ferris, Glovsky and Popeo.

“I have no plans to retire,” he told The Item.

On Saturday, Oct. 9 at Spinelli’s in Lynnfield, the longtime public servant will receive the “I Miglioti in Mens et Gesta,” or the “Best in Mind and Deed” award from Pirandello Lyceum. Founded in 1985, the nonprofit’s mission is to preserve Italo-American heritage and recognize outstanding Italians in Greater Boston who have made contributions to their profession and society. The honor is named for Luigi Pirandello, a Nobel-Prize winner for literature.

Bellotti has collected dozens of awards over his long career. In June, swimmers in the annual Frogman Swim Competition in Boston Harbor honored him for his service on June 6, 1944, when allied forces began the liberation of German-occupied Europe. Bellotti is the only remaining member of his unit from that fateful day. In 1981, the National Association of Attorneys General awarded him the prestigious Louis C. Wyman award, as the most outstanding attorney general in the United States.

But one prize has eluded Bellotti. He failed at three attempts to become governor. In 1964, he lost to Republican John Volpe. In 1970 and 1990, he sought the nomination of the Democratic party for governor, but was defeated in the primary in both elections, losing to Boston Mayor Kevin White and Boston University President John Silber, respectively.

Looking back, Bellotti said ugly rumors planted by opponents that linked him to the mafia doomed his bid for the corner office.

“It was very calculated,” he said. “They went from bar to bar telling patrons that I played cards with the mafia and took money from them. People would ask ‘Where is Bellotti getting the money for those big, beautiful Vote for Bellotti signs?’ I wouldn’t let members of the mob near me. I had no connection with mafia guys.’”

Following his defeat by Volpe in 1964, Bellotti said he received a call from a friend who told him that all 22 members of the family cast their ballot for him in the primary. But they switched in the final and voted for the GOP candidate.

“‘We had doubts, but I really want to apologize,’” Bellotti recalled him saying. “Unfortunately, there are still remnants of that kind of stereotyping today.”

Volpe, a fellow Italian, won by about 2,000 votes of the 2.3 million cast. But Bellotti said the difference was Volpe was well known to voters while he was just a young man starting a political career.

Still, Bellotti said he has no regrets and is thrilled to be recognized by the Italian group.

“They were founded to keep Italian culture alive and that’s a good thing,” he said.