- Join us in ‘Finding Mary’

- Finding Mary: The hunt begins

- Finding Mary: The search for relatives

- Finding Mary: How Frederick Douglass inspired my family search

- Finding Mary: Dead ends and revelations

- Finding Mary: A clash over values

- Finding Mary: A trip down slavery’s dark road

- Finding Mary: Faced with frustrations, I vow not to falter

- Finding Mary: A winding road paved by generosity

- Finding Mary: Turning troubling discoveries into positive paths

Genealogy resource 23andMe launched my journey into discovering my mother’s past. But the path I took on the journey wound through America’s South.

My new-found cousin, Bobbi Jo,* and I traveled from Charleston to Beaufort, S.C. to learn more about relatives in this region of the state. Along the way we passed massive marshes which were once rice plantations.

I struggled to comprehend how anyone could have worked in such oppressive conditions — muck, heat, humidity and mosquitoes.

In discussing these horrible conditions with Bobbi Jo, she mentioned that this was the reason why her planter ancestors built additional houses in Charleston and Beaufort — so that in the summer they could get away from the diseases caused by these mosquitoes.

The slaves they owned, however, didn’t have that luxury.

While driving past these former rice plantations, I recalled passages from “Slaves in the Family” by Edward Ball chronicling how his family produced rice in South Carolina for multiple generations. They were among the largest planters at that time and owned thousands of slaves who labored, unpaid, from their youth until they were no longer physically able to work.

Rice planters desired slaves from a certain part of West Africa, and I discovered that rice was cultivated in Senegal and the Niger River areas of the continent for up to 1,500 years.

Were the Ball family and other slave owners looking for slaves who already knew how to plant rice? In any case, the “Carolina Gold” rice they produced became highly desired in Europe and brought fortune to these slave owners.

During our drive, Bobbi Jo and I stopped to read a historic plaque on Route 17, which represented the exact spot where Harriet Tubman (known as the Moses of her people) and federal (Union) troops freed 700 enslaved people.

For the next few days, this tour of contrasts continued. Every conversation with Bobbi Jo about her slave-and-plantation-owner ancestors was counterpointed with stops at historic sites where African-American slaves had been freed.

When we arrived in Beaufort we immediately went to Bobbi Jo’s family’s graveyard — St. Helena’s graveyard — which held many of her relatives, slave owners, officials of the Confederate cause, as well as her relative, William Henry Cory, a spy for the Confederacy.

We stayed at her house in Beaufort, which had been owned by her family since 1810.

She gave me a walking tour of her neighborhood. She pointed out the house of her former next-door neighbor, the famous author Pat Conroy, whom she said she knew very well. He wrote “The Great Santini,” “The Water is Wide,” and the “Prince of Tides.”

She pointed out what once had been her grandmother’s home and served as the “Tidal Home” in the movie “Prince of Tides.” History unfolded at every turn in that neighborhood.

On the last day of my visit, Bobbi Jo brought me to the third floor of her home to show me messages carved into the walls by Union soldiers who were stationed there when Beaufort was captured by federal troops.

She also showed me what euphemistically she called “the slave quarters” — two crawl spaces measuring approximately four-feet by six-feet. I can’t imagine anyone finding any comfort there.

Next on our trip, we drove to the islands off of Beaufort. We first went to Lady’s Island next to St. Helena and then down to Hunting Island. Bobbi Jo was surprised to see the high water higher than she ever remembers it being. I guess global warming is taking its toll there too.

We went all the way out to Fripp Island, which was once owned by her Fripp ancestors in its entirety. She said now mostly “people from off” — mainly Northerners — lived there.

“What’s the difference between a Yankee and a damn Yankee?” Bobbi Jo asked me.

“I don’t know,” I replied.

“The Yankees visit and leave and the damn Yankees come visit and stay,” she said.

From Fripp Island, we traveled to Hunting Island and visited the Tombee Plantation. We visited cemeteries on most of these islands. One part of her family or another had lived on each island, had owned slaves, and were buried there.

One of the oldest cemeteries was on the Sams plantation sites and the cemetery on Dataw Island. This cemetery was also full of her ancestors who had owned the island and its large plantation.

A trip to Reconstruction Era National Park provided a very different perspective with former Beaufort Mayor Billy Keyserling serving as our tour guide.

We visited the Robert Smalls House. Robert Smalls had been born into slavery, but had freed himself, his crew and their families during the Civil War. He commandeered a Confederate transport ship, the “CSS Planter,” in Charleston Harbor and sailed it to the U.S. Navy enclave in Beaufort-Port Royal-Hilton Head area.

The Planter became a Union warship and Smalls’ example helped to convince President Abraham Lincoln to accept African-American soldiers into the Union Army. (Source: Wikipedia).

Our next stop was for lunch at the Foolish Frog, where they were dishing up delicious low-country, Southern-style seafood. They had an interesting saying on the shirts they sold there: “Putting the South in your mouth.”

Billy spent the rest of the day showing us every bit of history on display in the park. We went to the Brick Church and Penn Center and ended up at Port Royal, where, in November 1861, Union forces overwhelmed the Confederate defenses.

Cotton planters and their families fled to the mainland but most of the slaves, some 10,000, stayed to welcome the Union soldiers. (Source: Wikipedia). Bobbi Jo’s ancestors were among the cotton planters who left for the mainland.

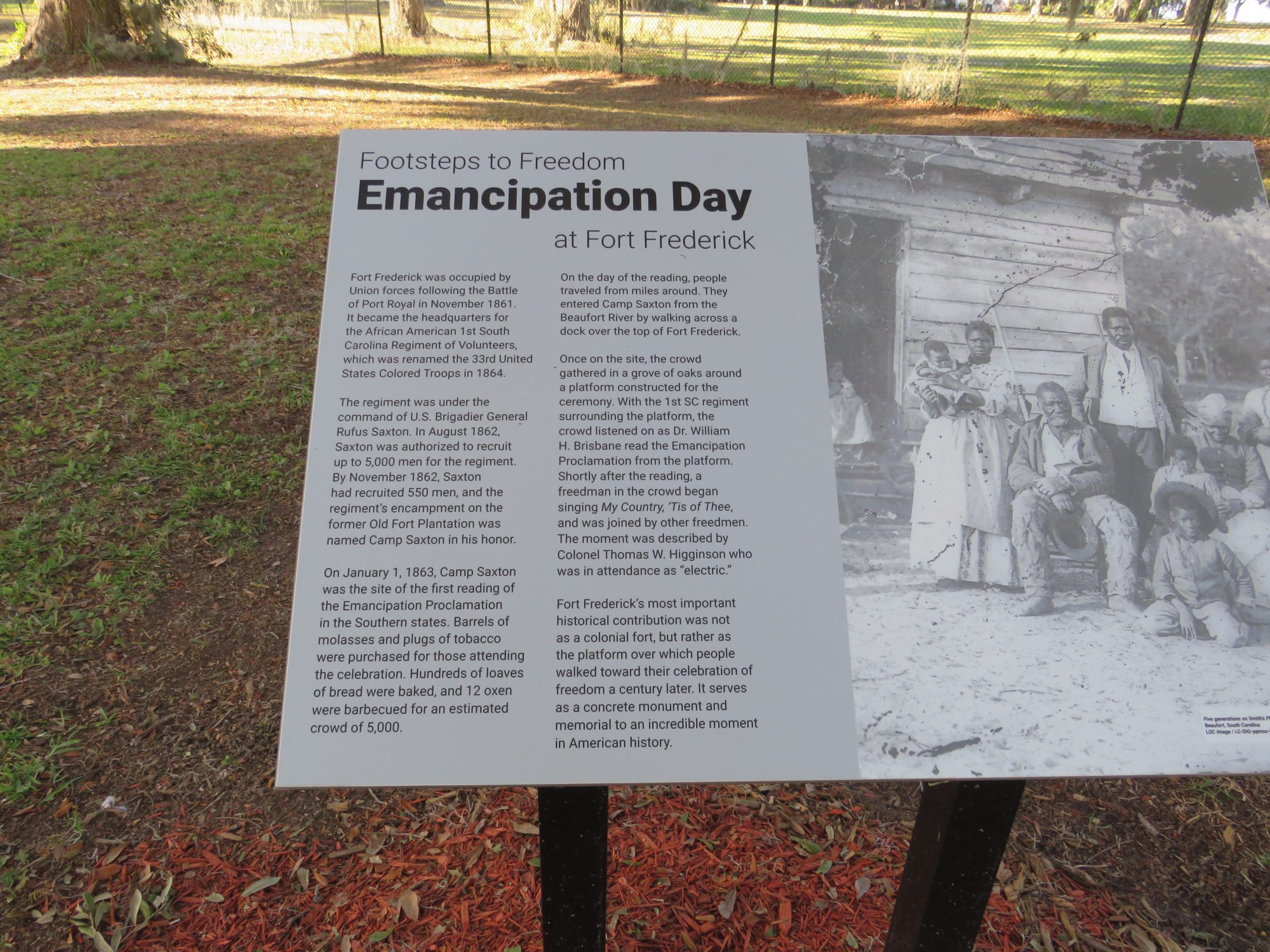

Billy mentioned that the site where we were standing, Port Royal, was the first place in the United States where the Emancipation Proclamation was read to freed slaves. On Jan. 1, 1863, thousands of freed slaves, believing they would not be free unless they heard the Emancipation Proclamation read, came by boat to celebrate their freedom. The purpose of Reconstruction was to grant full citizenship to African Americans equal to white citizens of that time. It came first to Beaufort and lasted longer there than in any other parts of the country where slavery had existed. It was a time that many African Americans succeeded, including in being elected to the United States Congress as well as to state legislatures.

All of this progress was set back by the establishment of Jim Crow laws enacted in these states. Jim Crow was a system of laws that legalized racial segregation in the American South between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and into the 1950s. (https://wwwbritannica.com).

I urge everyone to visit Reconstruction Era National Park. You are sure to come away with a greater appreciation for the sacrifices that were made for freedom won against slavery.

*The writer has used a pseudonym for privacy purposes.

NEXT: We visit the Department of Health and Environmental Control in Columbia, S.C. This is the main location of the state department that houses birth records and should hold the record showing my mom’s birth parents.