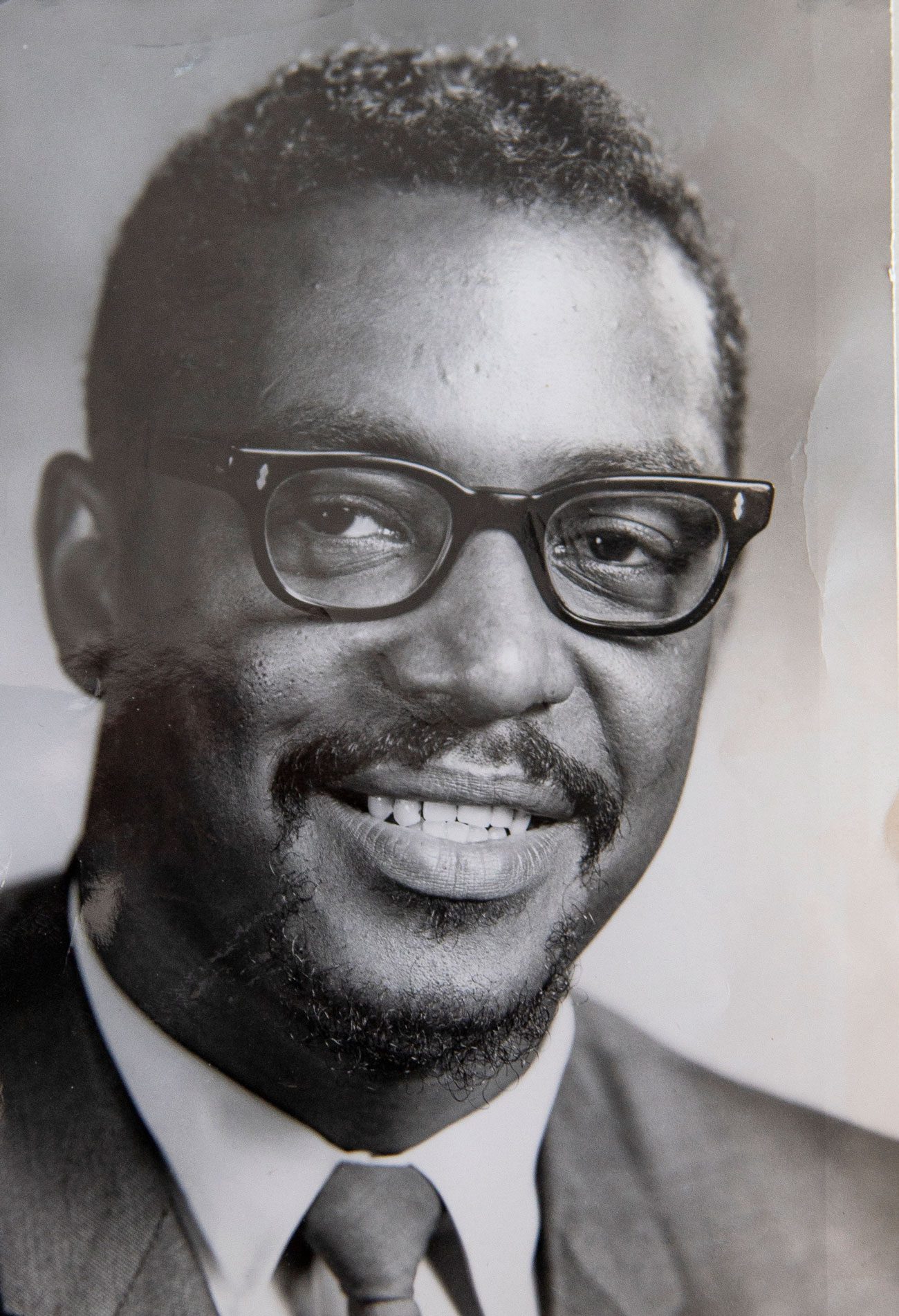

LYNN ― His name said it all.

Ed Battle ― community organizer, activist, advocate, husband, father, and friend ― was indeed a fighter who, in spite of the systemic odds against him, dedicated his life to the pursuit of equity and respect for all people.

There were many different phases of Battle’s life that are worthy of note ― including a stint in the Air Force during the Korean War that saw him achieve the country’s second-highest level of security clearance, and a position as H.P. Hood’s “first Black salesman.” In addition to these and many other periods of Battle’s long legacy, two are perhaps best remembered by those who admire him.

The first instance, now almost 60 years ago, remains achingly relevant in the minds of those across the country who seek racial justice.

The summer of 1964 was hot and sultry, and Mississippi was a powder keg. Battle, who died in 2015, had flown to Jackson to take part in “Hands Across the Cotton Curtain,” a voter-registration initiative of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that sought to empower Black Southerners disenfranchised by the region’s Jim Crow voting laws. (Battle was a lifelong NAACP member, and served as president of the North Shore chapter.)

“My wife, Amelia, was crying ‘don’t go!’ but I had to find out what was going on,” he recounted to The Daily Item in 2008. “I’d read about kids going down and helping out. They were white kids.”

Only a few weeks earlier, and less than a hundred miles away, three civil rights workers ― James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner ― were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in what was later termed the “Mississippi Burning” murders.

As for Battle, bullets flew less than 24 hours after his plane touched down at Jackson County Airport. The car in which he was escorted ― which also transported four other civil-rights leaders ― was found with small-caliber bullets in its windshield, though no one was hurt in the incident.

Danger was palpable that summer; one of Battle’s fellows was the brother of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, who was murdered only a year earlier. Charles Evers, Battle reported to The Daily Item in 1964, was under NAACP guard 24 hours a day, and for good reason. Another leader, the Rev. R.L.T. Smith, escaped bullets not a week earlier. It was in this environment that the NAACP leaders were to host the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

And Battle was to be one of his bodyguards.

It was rumored that the KKK was going to “raise hell” during King’s speech, and Battle was charged with “check(ing) every white person coming in.” On the night King was to address Jackson’s civil-rights advocates, he stood in Evers’ living room with Battle and others. The mood was tense ― and the .32-caliber stuffed into Battle’s waistband wasn’t helping matters much.

“He was frustrated and tired,” Battle recalled to the Item of King. According to the Lynner, King wasn’t happy with what he perceived to be the sluggish pace of change in the South, and Battle wasn’t happy with King’s immutable policy of civil disobedience.

Still, Battle recalled, when King got up to speak later that night, the tension in the atmosphere melted away.

“He pumped everybody up. The place went berserk,” Battle remembered. “I was proud as hell and scared as hell.”

To the great relief of Mrs. Amelia (Dykes) Battle, her husband was delivered back to her in one piece after a few weeks. While his time in Jackson might have been the most physically treacherous feat of his civil-rights work, his time as an advocate was only just beginning.

And this is the second instance in his legacy for which he is best remembered: His time spent as an advocate for the disenfranchised living in his city.

Within Battle’s resume is time spent as a Lynn Housing Authority (LHA) board member, a union-relations administrator ― and previously a counselor for disadvantaged employees ― at General Electric, and a social-services specialist at the Lynn Redevelopment Authority.

Battle’s tenure as a board member in the 1980s saw him arguing for housing equity on behalf of the city’s lower-income residents.

“Housing equity is an issue today, as it was back in the 1980s. (Battle) made sure that the process was equal and the same for everyone and that the opportunities were there for low-income people,” recalled Lynn Housing Authority and Neighborhood Development Executive Director Charlie Gaeta, who worked with Battle when the organization was known as the LHA. “He made certain that the playing field was level and that everyone had the same chance, and he was successful.”

Gaeta’s observation of Battle during their tenure together was that not only was he an advocate for the communities he sought to uplift ― he was an advocate to everyone.

“Eddie was a good spokesperson; he filled a great role being one of the leaders in the minority community in the city at that time,” Gaeta added. “At work, he was the go-to guy for a lot of people that felt that they weren’t being treated properly or needed further clarification and this came from both the tenants, the landlords and even the staff.”

“He was just a good soul,” he added. “He was a good man.”

Battle’s position as advocate for the disenfranchised, the marginalized, and the underserved was lifelong and the reason for this is likely the same as the reason he gave the Item in 1964 when a reporter asked him why he risked injury and death in Mississippi:

“To improve the future of my children.”