LYNN — When George Kostas Mazareas found out he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 2003, he was faced with a choice: Do you succumb or do you live?

As most people know by now, there is no cure for ALS, nor is there really a way to treat it. It is ultimately fatal, and Mazareas died from it Sunday at the age of 63 — 20 years after being diagnosed.

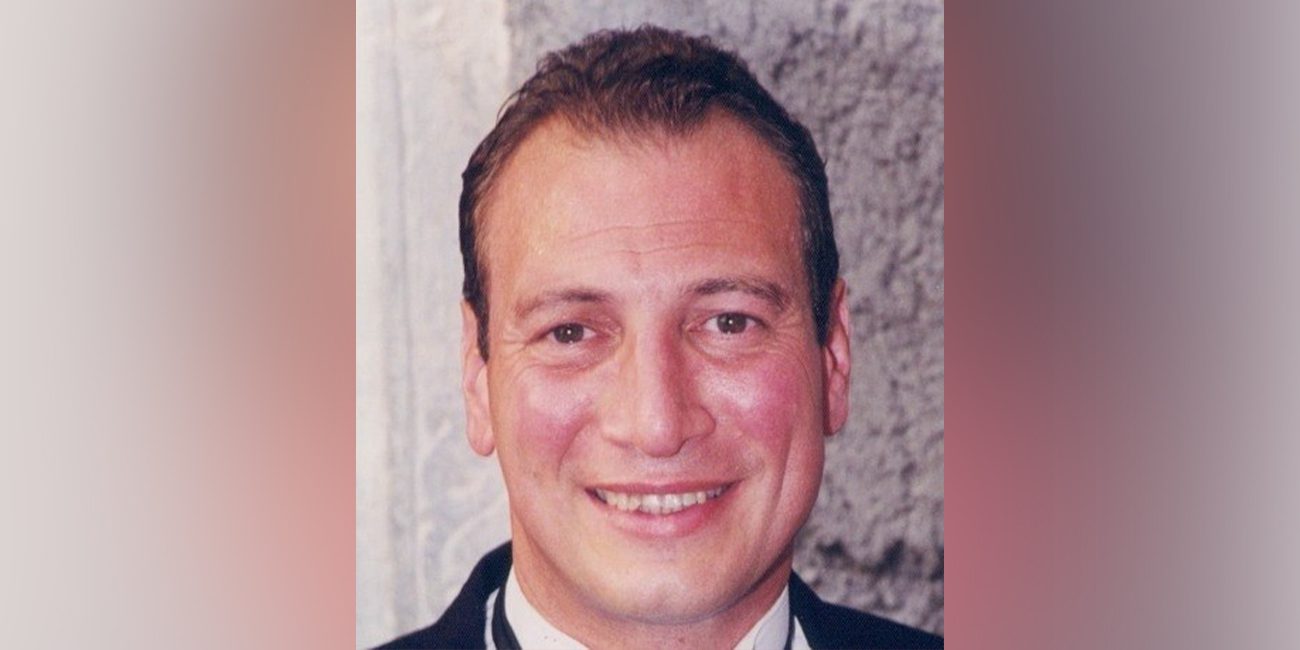

Mazareas was a man of many accomplishments, both athletically and academically. He played professional basketball in Greece, and was known for his feats on the court and in the gym. But it doesn’t end there. He was a husband, father, scholar, amateur astronomer, musician, history buff, city and town administrator who served on the School Committee, and so much more.

He was all these things when he was stricken by ALS, something he first came to notice when — ironically — he was playing basketball and couldn’t make a pass he’d made thousands of times, according to Andy Papagikos, perhaps his best friend.

Afterward, he was faced with the stark question of where to go from here. True to his personality, his friend Bill McDonald said, he didn’t just choose to go forward. He let the world know he was going forward.

“Strangely enough, during this ugly moment of truth, I was overcome with a surreal calm and sense of clarity,” Mazareas wrote in an Item opinion piece from 2003. “I had, at a very early age, decided to live my life by focusing on the positive things this world had to offer and not allowing myself to be weighed down by any negative elements.”

And whether it was Papagikos; Mazareas’ wife, Cynthia Tanner Mazareas; his cousin James Mazareas; Rich Kennedy, head of the Angel Fund for ALS research; or his childhood friend Steve Bulpett, all of them reinforced the idea that George Mazareas survived ALS for 20 years because of his attitude and courage.

“George really made a conscious decision to survive this disease as long as he possibly could,” Cynthia Tanner Mazareas said. “First and foremost because he had a child, and he wanted to be there with his daughter and raise her as best as he could. And he did.”

His daughter, Eleni Mazareas, was born the same year he was diagnosed with ALS. She is now a junior in college.

“He was an extraordinary father,” Cynthia Tanner Mazareas said. “He wanted to see her through as many milestones as he could. He lived in large part driven to be a father and be the best dad he could under the circumstances.”

However, he was also conscious that while he chose to live positively, the clock was ticking.

“He’d be making music tapes on the digital program Cynthia bought him,” said Papagikos. “He’d be racing the clock to do all these things.”

Kennedy, who worked closely with George Mazareas, said courage was the word that best defined him.

“I’ve never seen anyone with an attitude like his. He was never in a bad mood. Always classy. He looked forward to every single day,” he said.

“I have to give a lot of credit to Cynthia for standing by him the way she did. She was incredible,” Kennedy added.

And in those moments where everything may have overwhelmed him?

“He looked at things practically,” Kennedy said. “He figured out what was the best thing to do, always kept his head, and kept all priorities in order.”

One got the feeling that George Mazareas, growing up as a tall youngster in a gym full of shorter contemporaries, did not know what he had until his cousin educated him.

“After I got out of school, I was the athletic director at the church (St. George Greek Orthodox Church) and coached the GOYA (Greek Orthodox Youth Association) League Team,” said James Mazareas, a former Lynn Public Schools superintendent. “Here he is, up the top of the key shooting. I’m thinking, ‘How many tall Greek kids do you see?'”

“So I pulled him aside and told him what he should be doing, which was staying underneath and getting rebounds,” he added.

James Mazareas found out that a player of a similar build had learned how to get better at the inside by skipping rope with a weighted vest.

“So I made him do that for a half-hour every day,” he said.

“Finally, they’re playing in Beverly, and I see this big arm come over the rim and jam it in. It was George,” James Mazareas said. “And I figured, ‘He’s all set.'”

That foundation landed George Mazareas a spot in the National Hellenic Basketball Hall of Fame. However, his closest friends knew him as much more than a basketball player.

“Most of all, he was just the nicest, sweetest guy,” James Mazareas. “He had friends everywhere, and they stayed friends for life.”

The administrators of “the Harry,” the Harry Agganis basketball tournament held every April at St. George, present the “Maz Award” annually to the person in the Greek community who best demonstrates the passion, sportsmanship, and competitive spirit of George Mazareas.

George Mazareas knew what he was up against, his cousin said.

“He once said to me that as his daughter grew up and could do more and more, he could only do less and less,” James Mazareas said.

Bulpett was a teammate of George Mazareas’ on their GOYA team.

“Church was a very big part of his life,” Bulpett, who became a basketball correspondent for The Boston Herald, said. “And we played basketball all the time.”

But, Bulpett said, there was a more serious side to him,

“He wanted to talk about everything, and he could talk about everything,” Bulpett said. “Not in a debate kind of way, but in a conversational kind of way. We’d go on a car ride to Hellenic College for a tournament, and he’d talk about anything.”

All his friends spoke of his natural curiosity, whether it was setting up a telescope in his backyard, recommending reading material to his daughter, or studying music.

“If he got into something, he really got into it,” Papagikos said. “He’d be like ‘I’m on it,’ and he’d learn everything about it.”

That went for everything — including cars.

“He helped pick out my daughter’s car,” Cynthia Tanner Mazareas said. “He got online, did the research, and came up with two or three different kinds of cars for her to pick from.”

“George was who our grandparents told us we were supposed to be,” Bulpett said. “It was well known how the Greeks were the first ones to say the classroom should be next to the gymnasium — that the two were connected. Well, George lived that.”