By John G. Funchion

LYNN — For nearly 100 years, the Linotype machine was the mainstay of nearly every newspaper in the world. Its importance was so significant that it is still honored as one of the greatest inventions ever that helped disseminate knowledge in every Western society.

As a former member of that privileged world of journalism, I can attest to the fascination that it always held for me. Occasionally, after my daily written copy was worked over by desk editors at the Daily Evening Item in Lynn, I had to go down a flight from our newsroom and have the Linotype machine operator make some minor adjustment to the story.

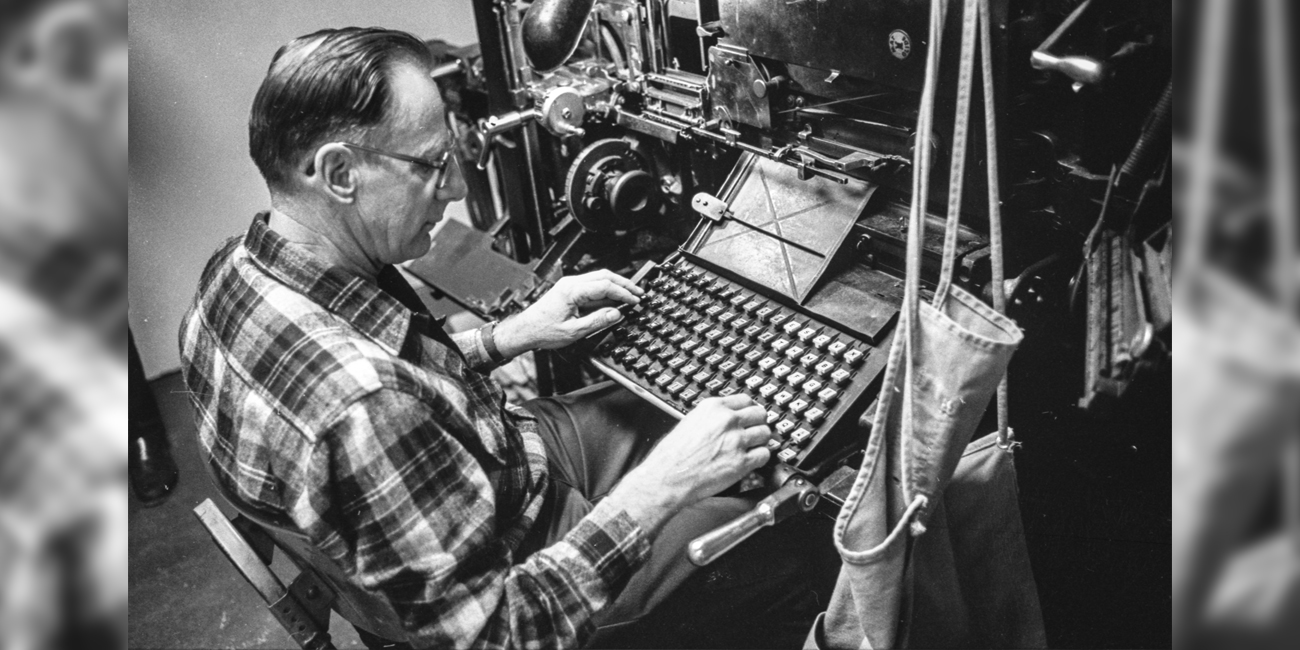

In doing so, I discovered and was always intrigued by his hot-lead metal pot hanging at the top left of that amazing machine. I always loved hearing the “clink-clink” sound of the lettered “matrices” sliding down a channel from a “magazine” on their way to be pressed into hot-lead letters and assembled at the bottom. Ultimately, when all the words of story were completed, the assembled metal words would be stamped into two half-cylindrical led master plates ready to be attached to the printing-press roll itself.

The Linotype was a six-foot tall, formidable-looking machine, approximately four feet wide and consisting of hundreds of mechanical parts and those channels accommodating those lead letters on their way to be assembled at the bottom of the run.

Every time I saw this incredible mechanical device that was responsible for the everyday dissemination of knowledge, it piqued my curiosity about who invented it.

It was a German clockmaker immigrant named Ottmar Mergenthaler (1854-1899) who invented the machine in Baltimore in 1884. It was the first device that could easily assemble a line of hot lead into a single line of type called a “slug.” After the slug was put into place for the half-cylinder master plates, it was returned to the hot-lead pot and melted down for further use. In effect, the invention was a 90-character keyboard typewriter connected to a foundry.

During the 19th century, 400 years after Gutenberg invented the printing press, there was feverish competition to find a faster typesetting product. Mergenthaler emerged as the winner with his invention.

Two years after its invention, in July 1886, the first commercially-used Linotype machine was installed in the printing office of The New York Tribune.

Though movable type was first invented by the Chinese centuries ago, the Linotype was the first invention of its type used to disseminate information since the development of the Gutenberg press in 1455.

The name Linotype comes from the fact that the machine produces an entire line of metal type; hence, ”line-o-type.” It was an unprecedented improvement over the universal, manual setting of type. Prior to its invention, no newspaper in the world could produce more than eight pages.

The machine was an incredible sensation at the Paris World Exposition in 1899. By 1904, 10,000 Linotype machines were in use; by 1954 that number had skyrocketed to 100,000 in use worldwide. They were the mainstay of the newspaper industry for nearly 100 years until the 1980s when the world of hot-metal typesetting systems was replaced by photo, digital, and computer typesetting.

Once during a conversation with a reportorial colleague in my younger years, I recall a prescient comment he made about computers. He said, “Isn’t it amazing that in the future, that our copy, via computers, would skip the hot-metal process and go digitally directly to the rolls of the printing press in the Press Room.” Wow!

The repercussions of that prediction meant that there would be no more of those highly-skilled operators of the Linotype machines. Those whose livelihoods depended on Mergenthaler’s invention ended up in the scrapheap of history.

Their highly-meaningful occupation, which produced billions of hot-lead words for millions of people around the world, folded into oblivion. Major and minor newspapers throughout the land retired their Linotype machines. And today, almost 50 years after their demise, it is rare that anybody knows anything about these magnificent purveyors of knowledge.

Amazingly, the last known newspaper to still use one in the United States is the Saguache Crescent located in Saguache, Colo. Its counterpart in Europe is Le Democrate de L’aisne in Vervin, France.

That 90-letter keyboard is quite different from standard keyboards today: black keys on the left are for lowercase letters; white keys on the right are for capital letters, and blue keys in the middle are for numbers and all sorts of punctuation. The casting material was an alloy of 85% lead, 11% antimony, and 4% tin. After the casting slug is used, it is automatically “lifted” back into the hot-lead hanging pot. The matrices that form the letters can be used 300,000 times before being discarded.

Another unique feature of the Linotype machine occasionally occurred when a squirt of molten-lead, which didn’t have any odor, spraying out through gaps of loose matrices, became hazardous to the operator. That’s when he grabbed the so-called “Hell Bucket” to capture the flowing menace. It was called the “Hell Bucket” because it would often “go to hell” and melt from the molten lead.

The venerable, once ubiquitous Linotype machines are now museum pieces. Their legacy is still preserved in two well-known museums: the National Museum of Industrial History, an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institute, in Bethlehem, Pa., and a lesser-known NMIH in Afton, Okla.

Years ago, when first introduced to the Linotype machine, I was ignorant of its profound influence on the dissemination of knowledge. So important was this machine that Thomas Edison termed it “The Eighth Wonder of the Industrial World.”

Most people in this computerized, digital, artificial-intelligence 21st century sadly have never heard of the Linotype machine. Like the inventions of the typewriter, sewing machine, microwave oven, dishwasher, and the magnetic resonance imaging machine (MRI), its effect was profound. From a single machine at any small newspaper to the 100 Linotypes once used by the Los Angeles Times, its significance was only realized by the millions of journalists who totally depended on that incredible mechanical contraption.

Now it is nearly 50 years gone. Within the technological limitations of another time, however, it served as the workhorse of spreading daily information throughout the Western world. And the 100,000 men and women who operated those machines with all of their learned and applied skills are now a part of history. An exciting history it was for me and all those pre-computerized journalists whose lives were filled with the sounds of clicking typewriters and the melodious “clink-clink” sounds of those magnificent Linotype machines.