Three weeks after the “killer poet” Norman Porter, who spent 20 years on the lam as a prison escapee, died on medical parole at the age of 83, his first victim’s fiancee reflected on her family’s 63-year search for justice and peace.

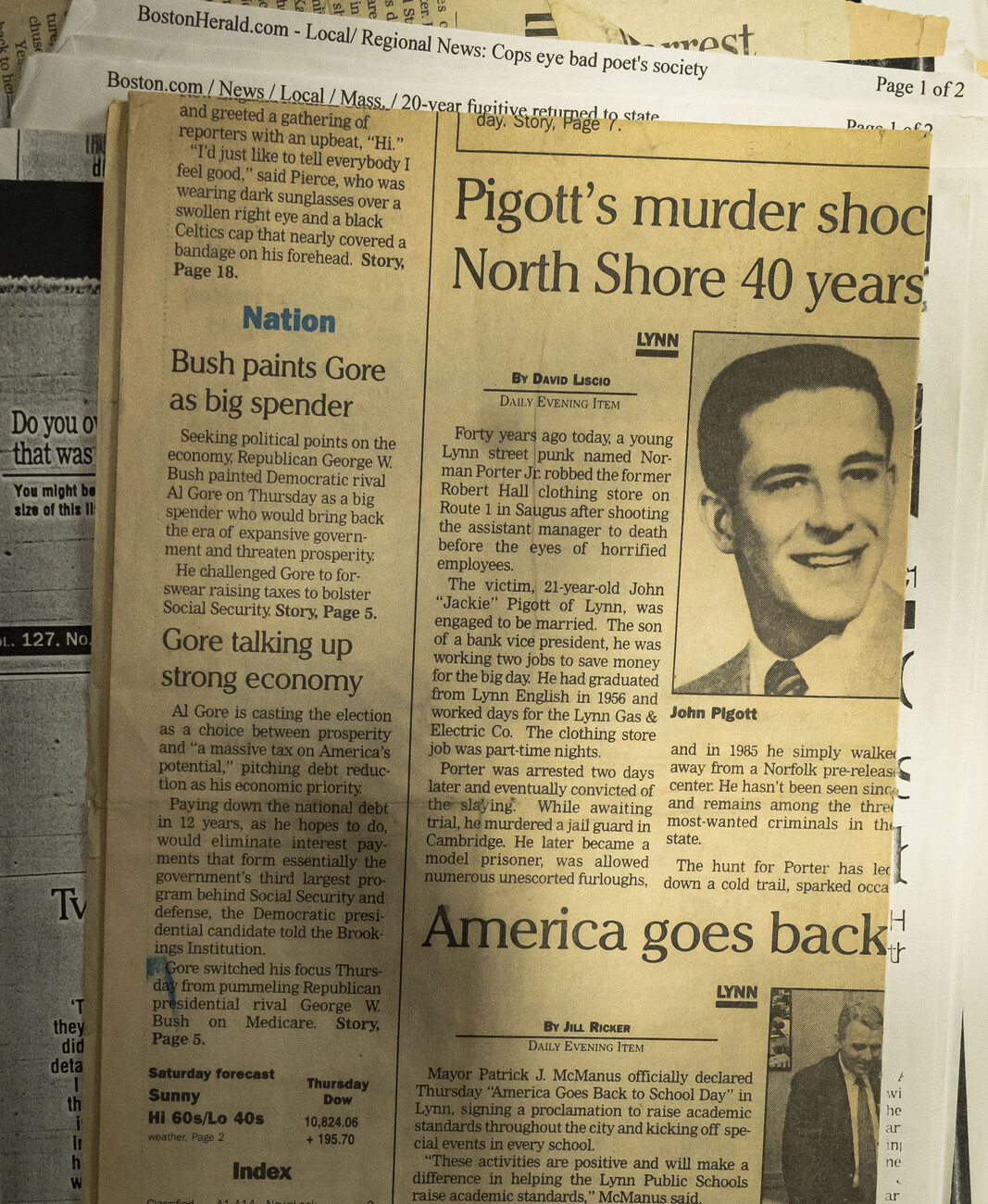

On Sept. 29, 1960, Porter, armed with a sawed-off shotgun, walked into the Robert Hall clothing store in Saugus alongside his accomplice, Theodore Mavor. The two men, wearing hats and bandanas, robbed the store at gunpoint, walking out with a little more than $400 in their pockets and leaving behind the body of Jackie Pigott, a 22-year-old store clerk from Lynn, who Porter fatally shot in the back of the neck.

Only 11 days before he was murdered, Pigott asked Claire Wilcox, then 19 years old, to marry him. The engaged couple, who Wilcox said were inseparable from the moment they met at the Essex Trust Company, had just begun planning their future together. Wilcox, now 82 years old, said she never truly recovered from the murder of her fiance.

“They say, ‘You will get over it, don’t worry about it.’ I’m proof positive that you don’t ever, ever get over it. You put it aside, I put it aside for 26 years of marriage, and then once this Porter thing came up, it brought a lot of it back,” Wilcox said. “Jackie and I were young and madly in love and it did a lot of damage to me emotionally for a long time… Norman Porter made a decision for me on the 29th of September, 1960. He chose the rest of my life for me.”

While being detained for Pigott’s murder at the Middlesex County Jail in East Cambridge, Porter conspired with another inmate, Edgar Cook, to escape. Using Porter’s gun, Cook shot and killed Jail Master David Robinson during the escape.

On the night of Porter’s escape, Wilcox said she was in the car driving with her father through Saugus when she learned of the jailbreak.

“The Saugus Police pulled us over as we were going through the square to go home, and my first reaction was, ‘Dad, what did you do?’ They were calling to tell him that I was going to be under police watch because Norman had escaped,” Wilcox said.

In 1962, Porter received multiple life sentences after being found guilty of murdering Pigott and Robinson. In 1980, he escaped custody and returned two days later. In 1985, however, he walked out of the Norfolk Pre-Release Center and never returned.

While evading law enforcement in Chicago for 20 years, Porter assumed the alias J.J. Jameson and worked as a poet and handyman. Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, Wilcox got married and had four children.

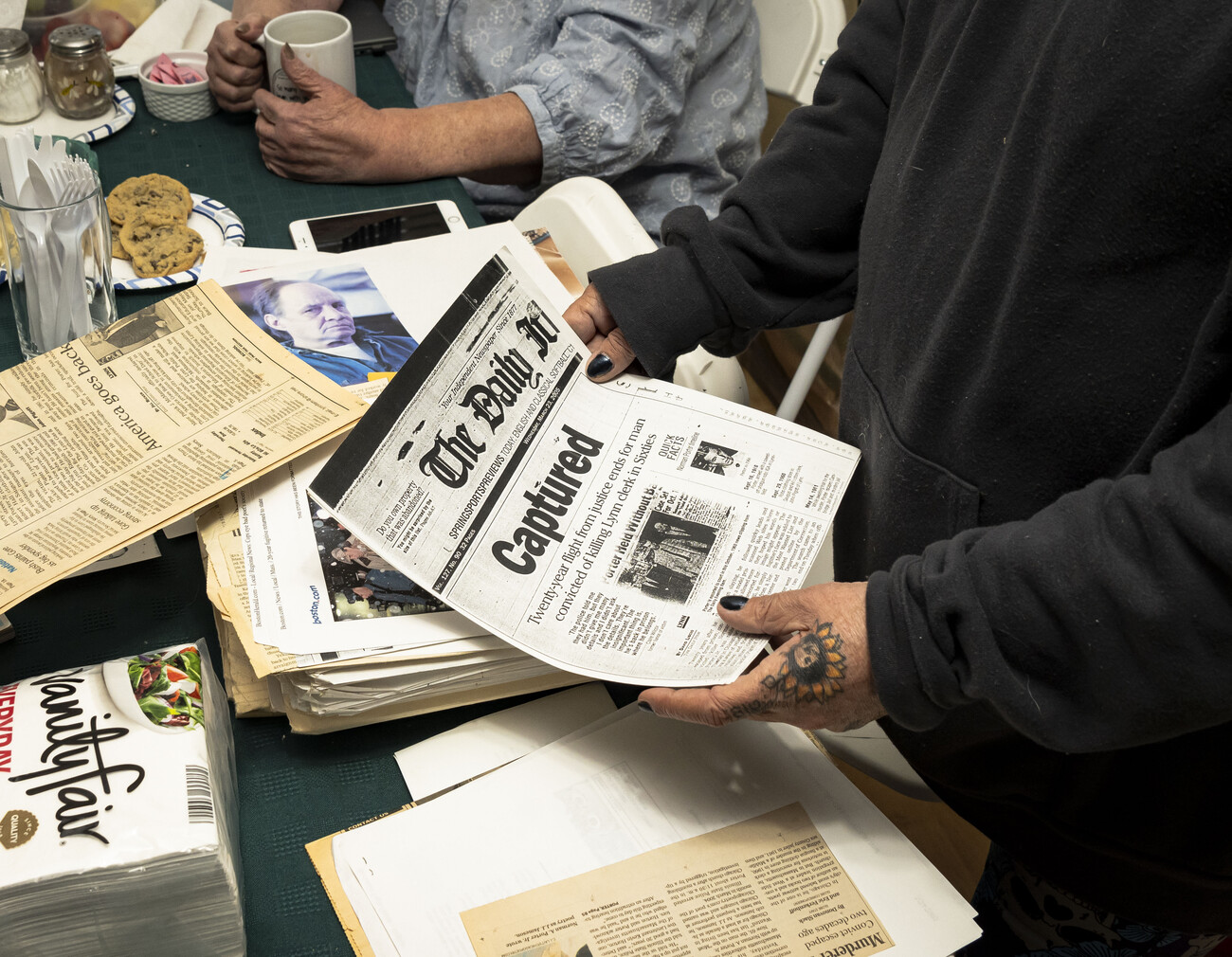

Seated in the kitchen of her Fitchburg home, Wilcox’s daughter Nancy Bray shuffled through a roughly 2-foot stack of newspaper and magazine clippings, mugshots, and court records on Porter. Although her mother sheltered Bray and her sister, Brenda Sekenski, from Pigott’s story, Bray claimed she first saw Pigott’s name when she and her sister were playing with a Ouija board.

“The spirit came on and said, ‘I love your mother.’ So we asked ‘What’s your name?’ And it spelled out J-A-C-K-I, and then his name, ” Bray said.

When Bray and her sister, who were respectively 12 and 15 years old at the time, went into the living room to ask Wilcox about the name Jackie Pigott, Bray said her mother’s face fell.

“She said, ‘Get in your room.’ So she came into the room and then she asked some questions that were absolutely confirmed for her, to the point where she was in tears. As children, we had no idea. This was not something that was common knowledge in our family,” Bray said.

Bray said when she found out about her mother’s murdered fiance, she stayed silent about the subject out of respect for her parents. However, she continued to play with the Ouija board and claims to have supernaturally contacted Pigott a few times.

It wasn’t until 1999 that Bray began investigating Porter, after she had a dream in which Pigott asked her to look into his killer. When Bray found Porter’s wanted poster and learned of his escape, she and Wilcox started to research the case extensively.

“I saw how important he was to her. Once she knew that this guy was out there and free, she was livid,” Bray said. “At that point, I was like, ‘Well, then I’m not going to stop until we get him back behind bars.’”

Scouring every library in the state for newspaper clippings and court documents, Bray and her family dove head first into the case.

Bray said her family stayed in close contact with law enforcement officers such as State Police Det. Paul Pellegrino, now-deceased State Police Lt. Kevin Horton, and State Corrections Officer Joe Peppe, even offering police clippings and documents after a flood damaged the department’s records.

It wasn’t until 2005, when Illinois State Police captured Porter in Chicago’s Third Unitarian Church, that Wilcox and Bray received a long-awaited phone call from the police.

“It was one of the officers from the Fugitive Apprehension Unit, and he said, ‘I just wanted to tell you and Nancy that we caught Norman,’” Wilcox said. “I put Nancy on the phone… she turned around and she walked out the door and said, ‘I’ll be right back.’ She came back with a cake. On the top of the cake was just the word ‘Caught’ written on it.”

From Porter’s capture until his death on Dec. 27, 2023, Wilcox and Bray attended and spoke at each of his parole hearings. Wilcox, who said Porter’s death made her feel as if a weight has been lifted off of her chest, said she hopes her story will make people think twice before engaging in crime or violence.

“You can try to forgive, that’s up to you whether you do or you don’t. But you can never forget… to this day, I still get flashbacks,” Wilcox said. “The same is true for the parents and neighbors and friends of all these young kids that are getting killed in schools … Norman had to saw the barrel off of that shotgun to make it do the damage that it did. He could not have bought it that way. Now 18-year-olds could go into a store and buy worse. These kinds of guns that can kill 15 to 20 people at a time.”