Dick Jauron was having lunch with the DeFelice brothers, Frank and Bob, at a bar in Pittsburgh. They were in town for a baseball tournament with the Boston Typos. As sons of a typographer – Anthony “Lefty” DeFelice worked in that position at Boston newspapers – Frank and Bob were on the team. Jauron wasn’t eligible to play, but he was happy to make the trip.

“Hanging out with him and Bob was the best,” said Jauron, who played with them on an Intercity League team. “That was one of the best experiences of my life just being around them at that tournament.”

The lunch took a turn when an over-served customer approached the table and told Jauron he wanted his sandwich. “It’s my sandwich and I’m not giving it to you,” Jauron told him.

The guy looked at Jauron and said, “For 50 cents, I’d cut your throat and take the sandwich.”

More than 50 years later, Jauron, a former NFL Coach of the Year with the Chicago Bears, still vividly recalls what happened next.

“The next thing I knew Frank came right over me, grabbed the guy by the neck and put him up against the bar,” he said. “It happened so fast. It was unbelievable.”

You almost have to feel bad for the guy, who went to the wrong table to pick on the wrong guy in front of the wrong coach. Jauron, who was heading into his senior year at Yale, learned a lot about his high school baseball coach.

“That was a great feeling for me,” he said.

That was Frank DeFelice, who always had his players’ backs in a coaching career that spanned almost 60 years.

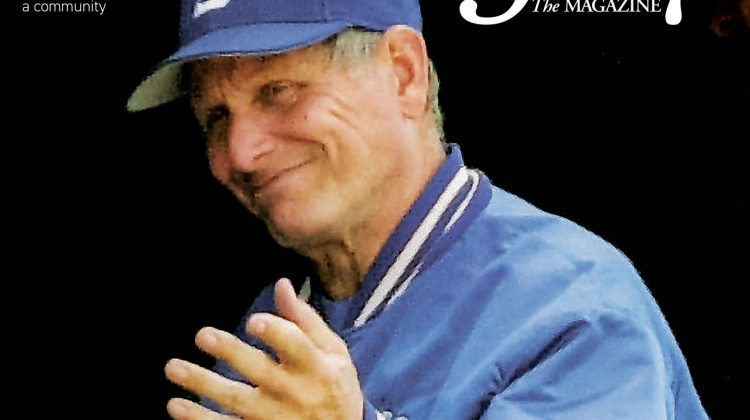

DeFelice died Tuesday at the age of 84, and while it is always hard to say goodbye to a coach and man of his stature, the notion that he might be starting to lose a little off of his fastball – which came through in the last of my thousands of conversations with him a few weeks before he died – allows his family and friends to be comforted by the fact that he is truly now safe at home.

A standout athlete at Winthrop High, Worcester Academy and Boston College, DeFelice will be remembered as one of the best coaches, and characters, ever to step on a gridiron or diamond. How great is it that, thanks to the efforts of Swampscott High coach Joe Caponigro and Steve Bulpett, one of his last times on the baseball field was on April 27 last year, when Frank DeFelice Diamond was officially dedicated.

“It’s tough to know he won’t be calling me to talk Big Blue baseball and letting me know that we bunt too much,” said Caponigro, who played for DeFelice. “His wins and longevity speak for themselves, but they don’t reflect the lessons we learned about life, physical and mental toughness, and work ethic. Coach was one of a kind and told it like he saw it. My appreciation for him did not peak until I was in his shoes as a high school baseball coach. When I was young and playing for him, I did not understand the magnitude of the impact that he had made on me.

Big Blue Nation and baseball in general lost a legend.”

Mike Lynch, the former Channel 5 sportscaster, had DeFelice as his head baseball coach and assistant football coach when he was a Big Blue standout.

“Discipline was A-number-one with him and there were no shortcuts,” Lynch said. “You had to do things the right way or do it over until you got it right. He was very demanding. It’s amazing how many of us remained his friend until the day he passed away and who think we are what we are thanks to people like Frank DeFelice.”

When it comes to DeFelice, the numbers are impressive – 465 wins, a state championship, three sectional titles, a .692 winning percentage in post-season play – but that will not be his ultimate legacy. Instead, it will be the legion of men, such as Lynch and Jauron, who have gone on to achieve an elite level of professional success and attribute at least some of it to their high school coach.

“Playing for Coach DeFelice was the first true meritocracy I experienced,” said Todd Kline, a member of the 1993 state championship team who is President, Commercial for the storied Chelsea Football Club in England and has worked in professional sports for more than 20 years. “He didn’t care about where you came from or your pedigree. All he cared about was how hard you worked. You got what you earned and you were not allowed to be a bad teammate. I didn’t realize until I got older how valuable that was.”

Like Kline, Jason Calichman wasn’t the most talented athlete in the Class of 1995 and he also had to prove himself – at one point just to make the team.

DeFelice wasn’t sure he was going to keep Calichman on the varsity in 1993 and he still hadn’t secured a spot as the team headed to Matignon for a pre-season scrimmage. The Warriors had one of the best pitchers in the state in Marc Desroches, so DeFelice made sure he would be pitching and he hit Calichman leadoff. It was sink-or-swim time.

Three solid at-bats later, Calichman had earned a spot on what would become a state championship team.

To illustrate the impact DeFelice had on his players, that isn’t even what Calichman remembers most about that day. Instead, it was what the coach told them at practice the day before: “It’s going to be a long day, boys, so you better bring a lunch. You can’t eat it on the bus and you can’t eat it on the field, so figure it out.”

Thirty years later, Calichman and his core group of friends still invoke that advice, with “figure it out” part of their text threads.

“As much as I had to win him over, he never closed the door on giving me a shot,” said Calichman, the Swampscott Middle School principal who will take over as superintendent of schools in July. He also served as varsity baseball coach at SHS. “When I got to college and things got hard for everyone else, it wasn’t that had for me, because I played for Coach DeFelice.”

In his role as an NFL Draft guru and college football expert, Todd McShay, also a 1995 SHS graduate, has spent time with some of the best coaches across the country. DeFelice was just different.

“Of all the coaches and people I’ve been around in sports, there’s nobody like him,” said McShay, who hosts The McShay Show podcast. “It was a challenge to play for him, but you learn as you get older that some of the most challenging coaches you wind up having the most appreciation for later in life.”

As the quarterback of the football team, McShay said he benefitted from having a football guy – and fierce competitor — as his baseball coach.

“He had a unique way of driving you, whether you were mad at him, confused or trying to prove him wrong” he said. “He was a mad scientist in his own way. He knew how to break us down and build us back up to get the most out of us.”

The best athlete in that group, and arguably one of the top five in school history, was Peter Woodfork, who as the senior vice president of Minor League Operations for Major League Baseball, is another Class of ’95 success story.

“Coach’s demand for excellence in all matters brought out the best in me,” said Woodfork, who played college baseball at Harvard. “He taught me invaluable life lessons on resiliency, discipline and maturity. His approach instilled in me the effort that was needed for life success.”

Woodfork’s father, Nelson, spent countless hours watching DeFelice make baseball practices interesting – no mean feat. He became a loyal and inseparable friend to DeFelice.

“You know in baseball that when there are runners on first and third with less two outs, that’s when all the fun starts,” he said. “I’d sit there and watch them work on that for hours. The only practices that never bored me were his baseball practices. Those teams were always prepared because that’s the way he did it.”

While baseball was DeFelice’s true love, he had a passion for football that made him want to coach the sport forever. Before he got married to Susan in 1968, his version of a prenuptial agreement was an unwritten contract that he would always coach football, which he did for almost 50 years.

He was the head coach at Swampscott High and Xaverian, but he really shined as an assistant, starting as Stan Bondelevitch’s line coach in 1966, the glory days of Big Blue football. He went on to coach at two other high schools and five colleges, including his alma mater, where he was on Jack Bicknell’s staff from 1982-90, coinciding with the unparalleled career of Doug Flutie.

“I’m very sorry to hear of Frank’s passing,” Bicknell said. “He was a great guy who was very helpful to me and our staff during our very enjoyable run with great teams during that time in BC football.”

For some of those years, DeFelice sat in the press box with offensive coordinator Tom Coughlin, who went on to win two Super Bowls as head coach of the New York Giants.

“Frank was a wonderful man to work with,” Coughlin said. “All he ever wanted to do was help in any way he could. I loved Frank’s attitude and the enthusiasm he brought to the field.”

Also on the BC staff was Swampscott native Barry Gallup, who hired DeFelice as an assistant when he became head coach at Northeastern.

“Frank was an amazing man. He loved to coach,” Gallup said. “He was hard on his players but they loved it. People loved working with him.”

After DeFelice’s tenure in Swampscott ended in 2005, thanks to a former superintendent who didn’t have the intestinal fortitude to stand tall when the naysayers came to his door, he was welcomed with open arms at Endicott College, where he was already coaching football. Baseball coach Larry Hiser brought him onto the staff and when Bryan Haley took over in 2008 he was happy to keep DeFelice around.

“His impact here has been immeasurable,” Haley said. “When I shared the news of his passing with alumni, a flood of stories came in. They have the same theme, humorous or teachable moments when he stepped in and taught someone something they needed to know. He impacted so many lives.”

That was not only as a coach, but also as a teacher over the course of 35 years, all but seven in Swampscott. One of his former colleagues at Swampscott Middle School was Bill Andrake, a decorated science teacher.

“Frank was very genuine,” Andrake said. “What you saw was what you got with him. He was man of integrity, which seems to be a rare commodity these days. He was true to himself.”

The person who spent the most time with DeFelice at school was Julie (Ryan) Halloran, who taught physical education in the same gym with him for 22 years.

“It was never boring,” said Halloran, who gained a husband out of the experience when I came in to speak to DeFelice about becoming his JV coach in 1989. “There was never a dull moment.”

A Division 1 athlete herself (Northeastern basketball), Halloran kept DeFelice in check – to whatever degree that was possible – prompting him to call her and his wife “the toughest competitors I’ve ever met.”

That JV baseball job led to a 35-year friendship that included multiple Las Vegas trips, high school basketball games and New Year’s Day football fests (before college football ruined its best day). But it always came back to baseball, either on the bench, with him behind the backstop in his lawn chair or on the phone. He was responsible for my becoming the manager of the Swampscott American Legion team, and always credited our success (state champs in 1996 and ’96) with making his program even better.

That’s flattering, but truth be told, under Frank DeFelice the Big Blue were very much a well-oiled machine, an orchestra with him as maestro, teaching young men how to play, but more important, how to conduct themselves.

He was one of one.