SAUGUS — The Historical Society held its October meeting, focusing on Louise Hawkes, who helped save the Saugus Iron Works. The historic Ironmaster’s house on the property was at risk of being shipped to Michigan for Henry Ford’s historic building museum.

“She was a relative of Adam Hawkes… Adam Hawkes was the first European settler in Saugus, even before it was called Saugus,” Historical Society President Laura Eisener said.

Eisener said that while the Iron Works is one of the town’s biggest tourist attractions, it might not be there if it weren’t for Hawkes.

“Certainly it wasn’t just a one-person effort, but if it weren’t for her extreme energy and enthusiasm, and maybe most of all her determination. She helped motivate people in town, people across the country, in fact, to help save the Iron Works and to set the stage for the National Park that we all enjoy in town today,” she said.

The first speaker was Samantha Hawkes Clark, who found out that she was somehow related to the Hawkes despite growing up in Maine. When Clark moved to Saugus, she had no clue who the Hawkes were and how they were connected. Her sister did some digging and found out that Adam Hawkes would be her ninth great-grandfather.

Clark connected with Janice Jarosz through the Daughters of the American Revolution Parson Roby Chapter, and Jarosz told her about Louise Hawkes.

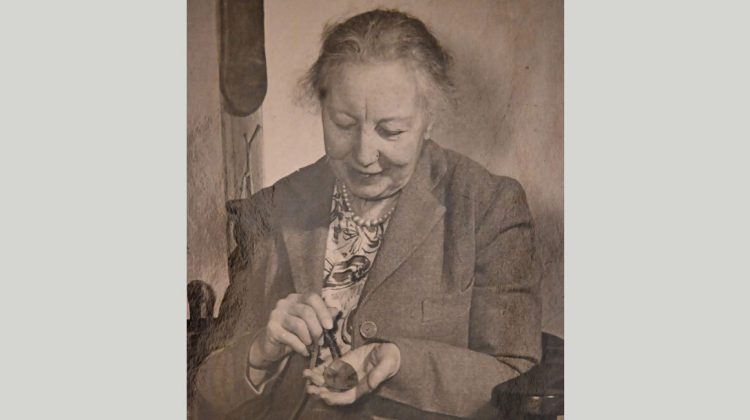

Hawkes was born in Malden on Feb. 3, 1882. She moved to Saugus and was the clerk for the Board of Assessors, according to fellow presenter Janice Jarosz. Hawkes was also the longest-serving president of the Saugus Historical Society, from 1936 until her death in 1960. She was also clerk of the First Iron Works Association.

Eisener said that the Iron Works had thrived in the 17th century for around a decade. It eventually went bankrupt due to flooding.

“The industrial buildings decayed, there was farming going on in Saugus, and then there was home building that changed the landscape somewhat. And maybe the most thorough change was road building in the intervening centuries… Central Street actually went right through the Iron Works property,” Eisener said.

Jarosz noted that there was nothing that truly memorialized Hawkes or her work.

“Nothing is named after her in this town. Not even a hydrant. There’s no females, except the Marleah E. Graves School. Everything is named after football players or hockey players… So that’s why we were so interested in trying to bring this together to make Louise come alive again,” Jarosz said.

The Historical Society’s Paul Kenworthy said that “Hawkes wanted the town to take the property (the Iron Works). The town couldn’t afford it, so she tried and tried and tried… There had been a bankruptcy in the mills, and a bank from New Hampshire owned the property. They had defaulted on a mortgage, and the bank had taken over. The bank sold the site of the Iron Works to the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1938.”

Eisener passed around a copy of the Iron Works deed, which included the signature of Hawkes, the Daughters of the American Revolution treasurer at the time.

With the town unable to afford the Iron Works, Hawkes began speaking with other groups, creating an interest in the site to raise money. Her outspokenness is what brought forth the funding.

“She talked to the president of SPNEA (The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities), which is now called Historic New England, and they were not able to pay for it all, but they thought that they might be able to spend some money on it,” Eisener said.

Another part of the funding came from what would be known as the First Iron Works Association.

The fight to keep the Ironmaster’s House in Saugus had begun, and the President of the First Iron Works Association traveled to Dearborn, Michigan, to strike a deal.

“Henry Ford agreed that if they could get all these people to contribute enough money to reimburse his alumni group for the money they had spent, that he would sell it to them, and the building could stay in Saugus,” Eisener said.

The town entered a limbo as residents wondered if the money could really be raised.

Town Meeting appropriated $4,000; the state legislature approved another $4,000; and by 1944, the residents raised another $4,000 with the help of a school penny drive started by Hawkes. They would eventually reach the $12,000 goal.

In September 1954, the industrial site opened to the public.

Hawkes remained involved with the Iron Works, giving tours when it opened and educating visitors to the grounds.